Identification of immune cells in healthy mouth lays groundwork for understanding disease

Maintaining the body’s barrier defenses at sites such as the skin and mucosal surfaces is critical for health and survival. These barriers are continually exposed to foreign substances and infectious agents, and are home to a diverse array of commensal microbes—microorganisms that cause no harm and are part of the normal flora. Immune cells at barrier sites performs the remarkable task of keeping peace with commensal microbes while fighting off dangerous pathogens.

To gain a better understanding of how the immune system achieves this delicate balance, researchers led by Niki M. Moutsopoulos, D.D.S., Ph.D., chief of the Oral Immunity and Infection Unit at NIH’s National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), in collaboration with Joanne E. Konkel, Ph.D., of the University of Manchester, set out to identify the types of immune cells present in the gingiva (gums), a key barrier site. Their findings appeared in the journal Mucosal Immunology.

The gingiva that lines the teeth is especially susceptible to infection because it lies close to the bacterial biofilms that coat the surface of the teeth. The gingiva is an important barrier site because it is continually exposed to large communities of bacteria called biofilms, which adhere to the teeth. In addition, the inner covering of the gingiva lining the teeth is especially thin, providing ready access to the underlying tissue.

By examining gingival biopsies from 50 young, healthy volunteers, the researchers observed a predominance of immune cells called T cells and neutrophils, as well as a sophisticated network of antigen-presenting cells and a small population of innate lymphoid cells, a type of cell not previously known to inhabit human gingiva.

Nicolas Dutzan, the study’s first author, was able to make these determinations thanks to advances in a technique called multicolor flow cytometry, which scientists use to identify cellular components. Current methodologies enabled Dutzan and colleagues to define as many as 15 different molecules per cell, which allowed them to identify definitively each cell’s type and to gain insight into how the cells may be functioning.

Moutsopoulos’ team also found evidence that many of the immune cells in healthy mouths, such as T cells and innate lymphoid cells, are tissue-resident, continually patrolling the area like a local police force. This finding is consistent with data from other studies, which have shown that barrier sites often rely heavily on local populations of immune cells rather than calling in the systemic immune system for protection.

To see how the pattern of immune cells changes with disease, the scientists next examined gingival biopsies from a small group of people with periodontitis, a serious inflammatory disease that, if left untreated, results in tissue damage and erosion of the bones that support the teeth. The diseased gingiva had elevated numbers of neutrophils, a type of immune cell that helps quell infections by engulfing bacteria. The researchers also saw increased levels of a molecule called IL-17, which recruits neutrophils to the site of infection.

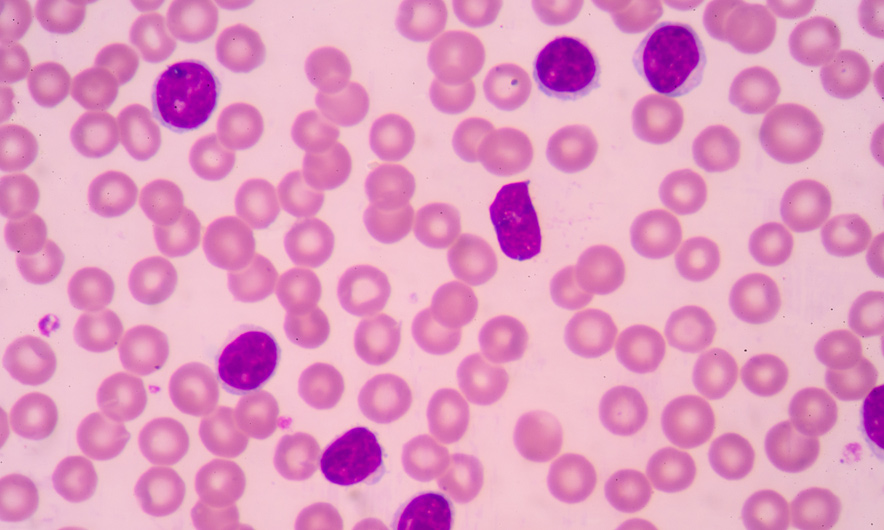

Healthy and periodontal disease gingival tissue taken from biopsies of study participants. Large numbers of immune cells are visible in the tissue damaged by periodontal disease. Courtesy of Niki M. Moutsopoulos, NIDCR.

While IL-17 is part of the host’s defense, if it is overproduced it may contribute to damaging inflammation. IL-17 is known to be associated with arthritis and other types of bone loss such as that seen in periodontitis, and inhibitors of the IL-7 pathway are used to treat psoriatic arthritis, a form of the disease associated with the skin condition, psoriasis. In future work, Dr. Moutsopoulos’ team aims to test the effectiveness of IL-17-like inhibitors in alleviating aggressive forms of periodontitis.

While landmark classical clinical studies have surveyed the major immune cell populations in the gingiva in certain inflammatory states, this study is the first to make use of current methodologies to perform an in-depth characterization of the immune cell network in healthy gingiva in humans.

“Our work is important because it provides a detailed picture of what the immune cell landscape looks like at this important barrier site under normal circumstances—before aging, infection or other problems arise,” said Moutsopoulos. “Knowing how these cells keep you healthy under ideal conditions sets the stage for our understanding of oral immunity and for being able to track changes that occur as disease begins and progresses. Ultimately, we expect to be able to use this information to identify novel drug targets and to develop new therapies for periodontitis and other diseases.”

Characterization of the human immune cell network at the gingival barrier. Dutzan N, Konkel JE, Greenwell-Wild T, Moutsopoulos NM. Mucosal Immunol. 2016 Jan 6. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.136. [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 26732676